The Waldorf Approach to Math

A multimodal and multidisciplinary approach is the key to our school’s mathematics program

Every child is capable of achieving in math. Just ask Jo Boaler, a Stanford education professor who is on the forefront of math education research. “We are all mathematics learners, and we can all develop active, inquiring relationships with mathematics,” Boaler writes in the paper Prove It to Me! “When we do, and mathematics becomes a creative, open space of inquiry, mathematics learners will find that they can do anything, and their mathematical ideas and thinking can extend to the sky—and beyond!” Boaler’s research shows that building a strong foundation in number sense—a feel for numbers and the ability to use them creatively—is key to becoming a successful math thinker, as is an ability to grasp big ideas and make connections between them.

At Marin Waldorf School, our approach to math is designed to do just that. Through a multidisciplinary, multilayered approach to math, starting at the earliest ages, students learn to see the joy and beauty in numbers, approach math work from many perspectives, and eventually build up to the conceptual ideas that fuel advanced-level math in middle school.

“A growing number of studies reveal the neural underpinning of what researchers call ‘embodied learning’ or ‘multimodal learning’—using your body to encode material more deeply by drawing, singing, or dancing, for example—and provide a window into how and why the approach works so well,” write the authors Youki Terada and Stephen Merrill in a 2025 article in Edutopia, who go on to demonstrate the many ways that movement and art can be used in support learning across subject areas—including math.

Here’s how we do it at Marin Waldorf School.

Early Childhood: Foundational Numeracy and Play

At Marin Waldorf School, our youngest students are engaged math learners—whether they know it or not! Starting at the earliest ages, our preschool and kindergarten teachers deliberately weave mathematical concepts into daily activities, helping students develop foundational numeracy and math skills.

"Watching the ease and joy of a preschool or kindergarten Waldorf classroom, it’s easy to assume that there is no set curriculum," says MWS math program director Julia McIlroy. "Each activity, game, song, and task in which they engage has been carefully curated to develop every aspect of a child’s mind, body, and heart." (Click here to read more from Ms. McIlroy on the Waldorf approach to math in early childhood.)

Early Childhood and Math: Math teacher and program coordinator Julia McIlroy details the approach to math education in the Waldorf preschool and kindergarten, which includes the use of fingers, which is known to correlate with math achievement.

Importantly, students are given ample time for free play, the best way for young children to explore and understand the world around them. More than any other activity, play naturally stimulates a child’s neural pathways, encouraging healthy cognitive and brain development. Among other compelling research, scientists have found that free, unstructured play builds connections in the prefrontal cortex, the brain’s executive control center. In an interview with Ed Source, Gennie Gorback, president of the California Kindergarten Association, explains, “Children learn high-level, intangible concepts such as the laws of gravity, conservation of liquids/mass, mathematical concepts such as more vs. less, all through hands-on, interactive play."

Elementary School: Multimodel Teaching and Number Sense

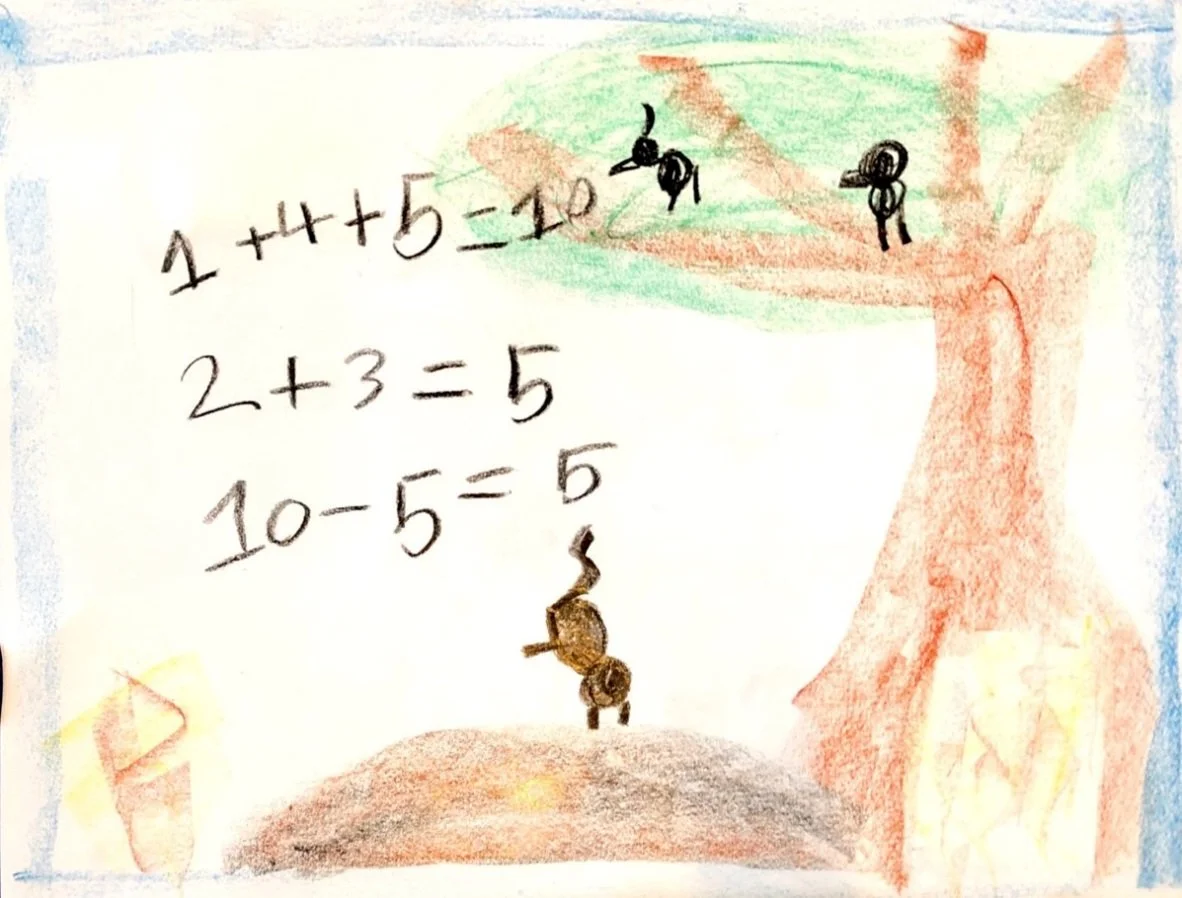

Stories, visual exercises, mental math games, skip counting, and the use of wood manipulatives are some of the many ways our teachers help build an awareness of numbers and an enthusiasm for math in the lower grades. Math exercises could range from skip counting while jumping rope in 1st grade to drawing decagons, decagrams, pentagons, and pentagrams to find the number patterns (and multiplication tables) in 2nd grade.

“Good mathematics teachers typically use visuals, manipulative and motion to enhance students’ understanding of mathematical concepts, and the US national organizations for mathematics, such as the National Council for the Teaching of Mathematics (NCTM) and the Mathematical Association of America (MAA) have long advocated for the use of multiple representations in students’ learning of mathematics,” write the researchers in the Seeing as Understanding: The Importance of Visual Mathematics for our Brain and Learning.

We also use story and imagination to give math context and meaning. For example, in second grade, teacher Ms. Terziev introduced the charming story of a mouse named Monsieur Fromage and his cheese cubes to helps bring a more abstract concept like place value to life. With this imaginative story to guide their activities, 2nd graders practice working with and solving problems using increasingly large numbers. (Click here to read more about the lesson.)

With a sense of wonder and creativity imbued in their math work, children are naturally drawn to the more complex problems they encounter as they move through the grades.

Middle School: Confidence and Concepts

By 6th grade, students are beginning to develop the ability to think abstractly, and our math curriculum meets their growing abilities with more complex concepts. Middle school math teacher Julia McIlroy aims to show students how mathematics is integral to all parts of life by looking at big ideas, patterns, and relationships between mathematical ideas and by grounding all subjects in experiential learning before moving to abstract principles.

"How do I develop a conceptual understanding? What I do is encourage more problem-solving and active learning. I want them to be engaged in learning, so they have confidence in themselves to go out and solve any problem that they encounter," says Ms. McIlroy. In 7th grade, for example, students measure large circles on campus to discover the relationship between the diameter and circumference (which we know as pi), before looking at it through the lenses of geometry, ratios, and algebra.

"What I’m trying to do is bring more complex tasks, where there are no immediate right or wrong answers. This prepares them for higher education and the workplace and keeps everyone engaged,” explains Ms. McIlroy. “If you have rich tasks, the students who may be behind academically can do something, and the students who are really high-achieving can take it to the highest levels.”

Group work is also a key component to Ms. McIlroy’s teaching, requiring students to work together to solve unfamiliar problems in both concrete and abstract situations—to find patterns, make conjectures, and test those conjectures, and to understand that mathematical structures are useful as representations of phenomena in the physical world.

Want to learn more about our math program?

Please click on these stories to read more about our creative, multifaceted approach to math education.

Early Childhood and Math: Math teacher and program coordinator Julia McIlroy details the approach to math education in the Waldorf preschool and kindergarten.

Beyond Numbers in Middle School Algebra: Creating a context can help students connect with material and understand how complex ideas evolved. In a recent algebra lesson, 7th graders learned about Mohammed ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, considered the "father of algebra," was a mathematician who worked in the House of Wisdom in Baghdad during the 800s CE.

A Second Grade Math Lesson: To teach the concept of place value, teacher Ms. Terziev introduced her students to Monsieur Fromage.

Meet Julia McIlroy, Bringing Magic to Middle School Math: Read this wonderful interview with Marin Waldorf School's math program coordinator and middle school math teacher Julia McIlroy.

First Grade Math: Bird by Bird: Students unite art and math with story-problems in first grade.