Meet Julia McIlroy: Bringing Magic to Middle School Math

Marin Waldorf School’s marvelous math teacher, Julia McIlroy, has always been drawn to mathematics and sciences, but she’s also seen the world from many other perspectives: as a teacher, as a prison volunteer, as a public defender, and as a mother. As a graduate of Summerfield Waldorf School in Santa Rosa (which she describes as a “beautiful experience”), Ms. McIlroy learned to have a complex view of the world—and that’s just what she thinks the best students can bring to STEM fields. Learn more about her upbringing, her Waldorf education, her life as a public defender, and her approach to math education in the interview below.

Let’s start by talking a little bit about your childhood and education. Where did you grow up?

I grew up on a vineyard outside of Healdsburg, before Healdsburg was posh. My grandpa was a cardiologist, but he had a dream of owning a vineyard, so in the 70s he bought forty-five acres along the Russian River and transformed it into Chardonnay, Zinfandel, and Pinot Noir grapes. So that’s where I grew up—wild and free, roaming the countryside and playing in a winery.

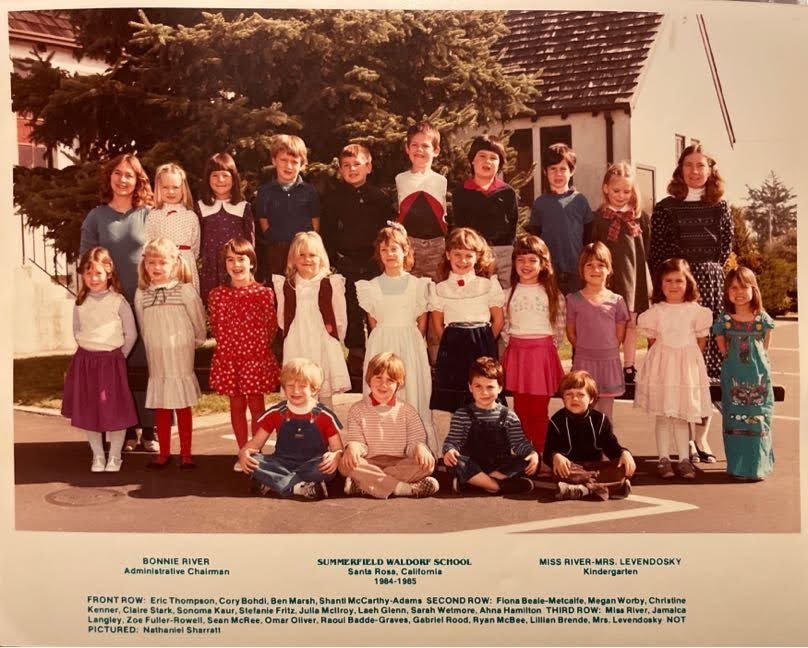

My mom is a microbiologist and food chemist, so she was working when I was young and they had to find a school for me. They eventually found Summerfield Waldorf kindergarten. I remember the first time I visited the kindergarten: the classroom was so warm and inviting. You wanted to stay there for the rest of your life.

My mom knew immediately that this is where we were supposed to be. My dad was not so convinced. But he came along. Eventually they both ended up going through the Waldorf teacher training and my mom is now a special education teacher.

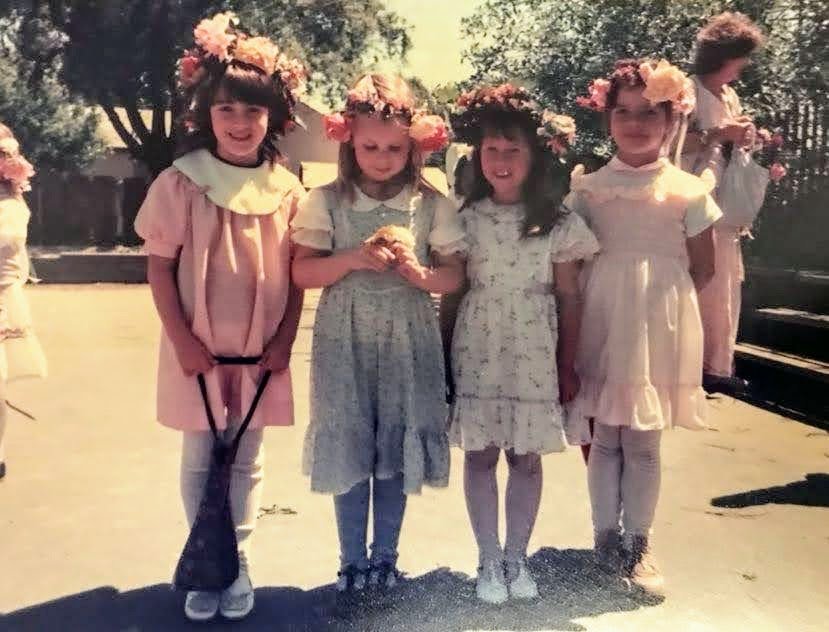

I remember kindergarten vividly: making soup and honey buns, building fairy houses in the field, and climbing trees and rocks. I still have the birthday book of drawings from all my classmates!

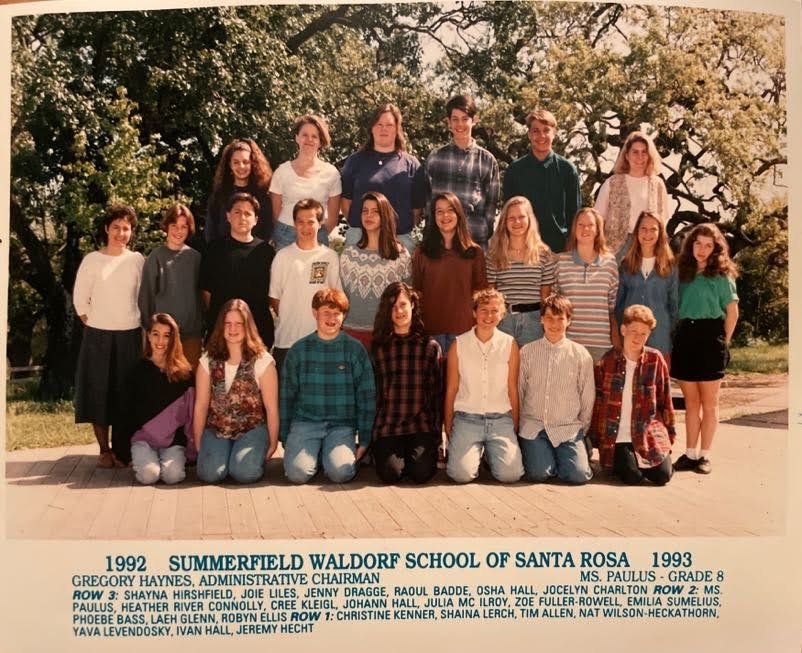

I went to Summerfield through 12th grade. It was a rich experience and prepared me so well for college and law school. In fact, college felt a little easy after my rigorous high school classes. In high school, I read Emerson and Thoreau, studied Russian literature, and every year took physics and chemistry. The early and middle grades were similarly rich and I developed a deep love of learning and a strong foundation that is still benefiting me today.

Where did life take you after high school?

In high school, I had amazing teachers and I wanted to do and be everything. My biology teacher was particularly inspiring, and I thought I was going to be a biologist or maybe a doctor. Then I went to college and I really loved learning about people and how people worked, so I became more interested in psychology and sociology. There was a program that was asking for volunteers to go to prisons and interview women who had been battered. A new law at the time allowed for women who had been battered to have their sentences reduced. Our job was to go into the prisons and take their entire life history.

First of all, it’s so hard to be in a prison. Even visiting for a few hours is awful. And then the women would share their life history with me. Every one was a life of trauma and abuse that started at a young age. And then they would encounter the legal system, and the legal system would essentially do the same. They were punished for having lived a life of abuse. It was traumatizing, just hearing it. I felt I had to help. I couldn’t let the system just keep going as it was.

So I went to law school and I became a public defender. I did that for many years. What I learned is that you can help individual people, but it’s much harder to change the system. I’d keep seeing the same situations — and even the same clients — over and over again, and every time I felt that, yes, I can make this person feel seen and heard, but I can’t affect the entire system. At some point, it becomes a burden. It weighs you down.

I was teaching all along, but I think that’s really why I started spending more time teaching. Because teaching is a creative, hopeful exercise. Helping students reach their potential was healing in so many ways.

What other teaching jobs did you have?

I worked in the math department in college, and I worked as a high school substitute teacher and remedial teacher. When I was a public defender, I worked at Empire College in Santa Rosa teaching paralegals. And I helped create the San Rafael High School mock trial program.

There’s a really active mock trial program in the county, but San Rafael High School didn’t have one. We want more diversity in the legal profession, but if we exclude one of the schools in Marin that has a lot of diversity, you’re missing an opportunity. So we decided to start a mock trial program to get more students of color engaged and so they know that law is a possibility for them.

The students were remarkable—better than many attorneys that I knew. That’s how good they were! Every year there is a mock trial competition in Marin in front of real judges where the high schools compete against each other to go to the state championship. I encourage my students in middle school to go see it, because if they go to high school in Marin, they can participate.

So let’s talk about middle school! As a teacher, how do you approach math?

I am passionate about math education. My number one goal is to keep students interested and engaged in math so they will continue on with it in college and beyond. I want to have as many of our students go into STEM fields as we possibly can. Our students have a complex and ethical view of the world—I think having them in science and technology is really essential for our future.

Math education hasn’t changed in over 100 years. The timing has changed: Schools keep shifting the curriculum younger and younger because they think that will prepare students for harder math, but it’s actually backfiring. What colleges are finding is that students aren’t actually prepared because they’re advancing in math too early and their brain development hasn’t caught up.

If you look at the countries that are very successful in math, they often wait until kids are 7 years old to do any sort of formal math instruction. The other thing they’re doing is teaching math more conceptually. What I find is that once students figure out how to solve a problem, they’ll be able to repeat that problem 30 times. But they still won’t understand what it means. They can get a nonsensical answer and not even realize it because they’re not thinking conceptually.

How do I develop a conceptual understanding? What I do is encourage more problem-solving and active learning. I want them to be engaged in learning, so they have confidence in themselves to go out and solve any problem that they encounter.

Part of that is having more complex work. Not just having worksheets with repetitive problems, but having complex tasks, where there are no immediate right or wrong answers. This prepares them for higher education and the workplace and keeps everyone engaged. If you have rich tasks, the students who may be behind academically can do something, and the students who are really high-achieving can take it to higher levels.

Unfortunately students believe that math is procedural work like times tables and fractions. While those are important, that’s not how math is in the real world. I went to a training at Stanford last week with a professor who is at the forefront of mathematics education, and changing mathematics education here in California and in the world. She told us about how she went to a PhD defense presentation in which there wasn’t even one number involved. It was for a PhD in mathematics, but there wasn’t even one number!

Math is really a creative, visual subject. But it is not taught that way. In fact, one of the most incredible mathematicians – she was the only woman to ever win the Fields Medal, which is like the Nobel Prize for math – would draw everything she was working on. Her daughter, who was 4 or 5 at the time, thought she was an artist because she was always drawing at the kitchen table.

What we think of as math is not really what higher level math is. So I tell my students that just because you struggle with this one tiny aspect of math, it doesn’t mean that you can’t think mathematically and be a mathematician. It is so gratifying to watch my students become fully engaged in math and persevere with difficult material. Teaching is truly such a joy.

Interview by Julie Meade. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.